Why Trauma Healing Is at the Heart of My Work

It was my personal journey through healing my own Complex Trauma that led me to the deeply meaningful and fulfilling work I do today. Alhamdulillah, it is such an honour to provide therapy to Muslim women around the world. Trauma is at the heart of my work because I have witnessed its significant impact within my own family and because it is so widespread among the Muslim women I am honoured to serve. It is important to me to provide the most effective and compassionate care to my sisters in Islam. For this reason, I am committed to ongoing training and continually expanding my expertise in this area.

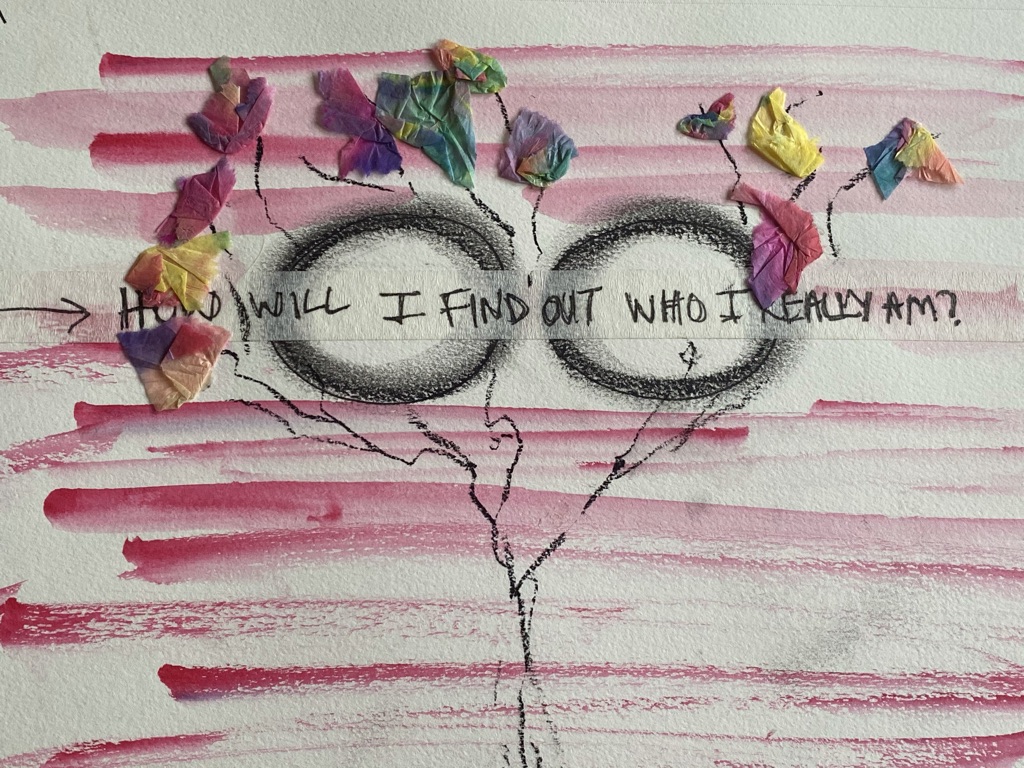

I am passionate about continuing this work, seeking Allah’s guidance, to develop a richer understanding of how Islamic psychology, in combination with Expressive Arts Therapy and other therapeutic modalities, can support trauma survivors. This integrative approach helps them engage with and process their difficult stories in ways that free them from being defined by their past or believing their experiences determine the outcomes of their lives. SubhanAllah, it is a transformative process that reminds us of Allah’s promise: “For indeed, with hardship comes ease.” (Qur’an 94:6)

Over the course of decades, I worked with a variety of therapists and trauma specialists, each offering different tools and perspectives. But I also learned something incredibly painful: just because someone calls themselves trauma-informed doesn’t mean they truly understand trauma, especially when it’s complex. In fact, some well-meaning professionals caused me severe harm—not out of malice, but simply because they lacked the knowledge and sensitivity that trauma work requires.

After over 15 years of talk therapy, I began to notice something unsettling: instead of feeling better, my trauma felt bigger, louder, and more consuming. It finally dawned on me why. The more we pour our thoughts and energy into something, the more space we give it to grow. As the saying goes, where attention goes, energy flows.

I started reflecting on Einstein’s definition of insanity: “Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” The longer I stayed in the cycle of talk therapy, the clearer it became—it wasn’t leading me to healing, but deeper into frustration and exhaustion. What once felt hopeful now felt repetitive, like walking the same path expecting it to lead somewhere new. It wasn’t that I was failing; it was that this approach wasn’t what my healing needed. It was time to step off that path and explore new ways forward.

This shift marked a turning point in my healing journey. And it’s this lesson—this hard-won understanding—that I now carry into my work with others.

Understanding Trauma

Before we delve into trauma healing, it’s essential to clarify what we mean by trauma. The term has become common in everyday conversations, often used to describe mildly stressful or uncomfortable experiences. Phrases like “That conversation was traumatizing” or “That movie was traumatic” have become normalized, even when referring to situations that, while difficult, don’t meet the threshold of trauma. This casual use can unintentionally diminish the weight of what trauma truly represents—a profound psychological wound that overwhelms one’s ability to cope. By grounding ourselves in a clear understanding of trauma, we create a foundation for meaningful exploration and healing.

Years ago, I encountered an insightful analogy about trauma: “To define all adversities as traumas is like seeing all collisions as smashes. People collide with misfortune all the time—sometimes it smashes them, but often they merely make contact.” Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, a leading psychiatrist in trauma research and treatment, frequently explains how an event might cause trauma in one person but not in another. This variability underscores the importance of understanding trauma beyond its casual use.

The definition I use in psychoeducation and client work comes from van der Kolk: “Trauma is something that overwhelms one’s coping capacities.” Trauma, he explains, is an injury. The word itself comes from the Greek root meaning “wound.” When we think of an injury, we typically see it as something that can heal with the right care and time. Yet many of the clients I’ve worked with feel stuck, believing they’ll never “get back to their old selves” or be able to function again. This belief, while deeply felt, is often untrue. Healing is not only possible but a testament to Allah’s mercy and wisdom.

When the Body Remembers: How Trauma Manifests Physically

Emotional trauma often leaves scars that extend beyond the mind, embedding themselves deep within the body. This intricate interplay between emotional distress and physical manifestation can lead to chronic pain, fatigue, migraines, gastrointestinal issues, and other elusive health concerns that often defy conventional medical explanations.

When we experience trauma, our body instinctively responds to protect us—flooding us with stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline to prepare for danger. But if the trauma is prolonged or remains unprocessed, this survival response can become stuck in overdrive. Over time, the nervous system struggles to return to balance, and the body begins to carry the burden of the trauma.

This disruption can contribute to conditions like fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, or persistent muscle tension. You might notice unexplained physical symptoms—tightness in your jaw, knots in your shoulders, a heavy sensation in your stomach, or chronic fatigue. These holding patterns often keep us stuck in cycles of dissociation, disconnected from our hearts, and unable to fully exhale.

But when we gently allow ourselves to move through these physical sensations—whether through breath, movement, or body awareness—we begin to feel energy shift. It’s often described as a deep breath finally being released or tension lifting from places we didn’t realize were holding it. The heart softens, expands, and opens again, creating space for ease and stillness.

Trauma isn’t just the event itself—it’s the impact it leaves behind. It’s the patterns our nervous system adopts to keep us safe, and the ways those patterns linger long after the danger has passed. True healing happens when we allow these energies to be processed, released, and integrated. This perspective shifts us from feeling like passive victims of our experiences to active participants in our healing—a powerful reminder of our capacity to heal, with Allah’s help and mercy.

At Muslimah Therapy, we approach healing with gentleness and deep care. Through Expressive Arts Therapy, body awareness techniques, and a holistic Islamic framework, we create spaces where your body’s messages can be honoured. Healing isn’t about silencing or dismissing pain—it’s about creating safety, inside and out, so your nervous system can exhale and your body can begin to trust again.

Reconnection Begins with Safety

True safety starts with recognizing that our ultimate refuge is with Allah, As-Salam (The Source of Peace) and Al-Hafiz (The Preserver). While we work to create safety within ourselves, we are reminded that Allah’s protection and peace are always available to us, regardless of how turbulent our internal or external world may feel.

From this foundation of trust, we can gently cultivate safety within ourselves. This often involves tuning into our bodies, noticing sensations, and observing where we hold tension, constriction, or unease. It’s in these quiet moments of curiosity, without judgment, that we begin to rebuild trust with ourselves. Healing isn’t about forcing safety; it’s about nurturing it, step by step, moment by moment.

When we learn to create an internal sense of safety, we also start to feel safer with others, in our relationships, and in the spaces we inhabit. This ripple effect allows us to approach our healing with compassion rather than force, and trust rather than fear. As we reconnect with ourselves, we also reconnect with Allah, the ultimate source of peace and refuge.

In this space of safety, healing can begin to take root and flourish.

Ultimately, safety starts with gentle noticing and invites us to approach ourselves with compassion and trust, echoing Allah’s promise to us: “Allah does not burden a soul beyond that it can bear.” (Qur’an 2:286)

Healing as an Act of Worship

Healing from trauma is not merely about feeling better—it’s an act of devotion. It’s an expression of tawakkul, trusting Allah’s plan even when the path feels uncertain or the pain feels unbearable. Choosing to heal is choosing to honour the trust Allah has given us in caring for our bodies, minds, and souls.

When we engage in healing, we are not simply fixing what feels broken; we are aligning ourselves with Allah’s infinite mercy and wisdom. Every small step towards healing—a moment of gentleness with ourselves, a breath taken with intention, a prayer whispered in vulnerability—is an act of worship.

Healing teaches us patience (sabr), gratitude (shukr), and reliance (tawakkul). It reminds us that we are never truly alone, no matter how isolating our pain might feel. Allah is with us in every moment, in every breath, in every tear we shed.

Ya Rabb, make this journey one of healing, trust, and nearness to You. Ameen.